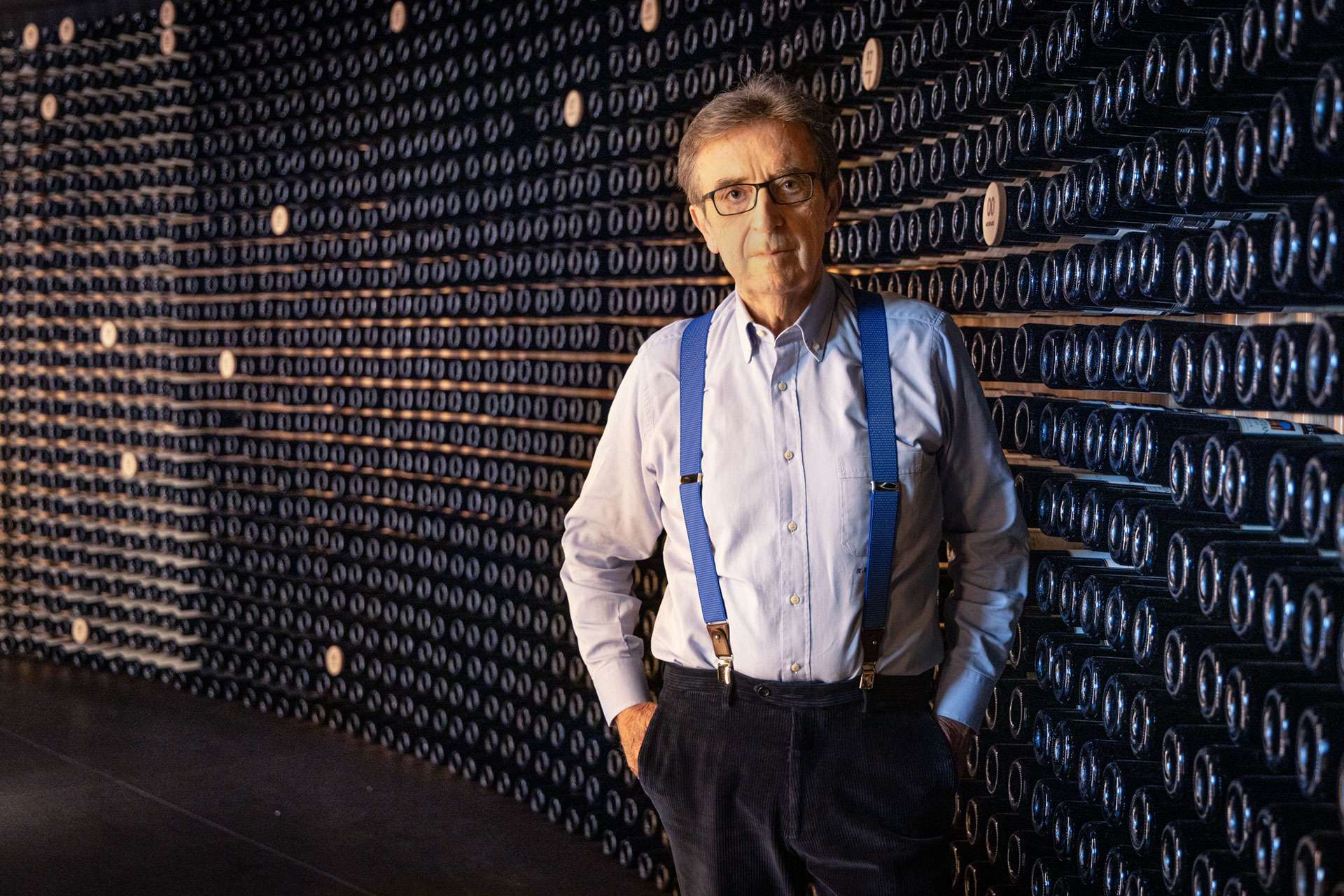

Riccardo Cotarella highlights the urgent need for a more entrepreneurial approach in the Italian wine sector. From better storytelling to aligning with market trends and embracing organic certification, Cotarella stresses that production alone is not enough. Italian wineries must evolve, communicate effectively, and strategically compete with global players—especially France—to truly unlock their full potential.

We explored key issues with Riccardo Cotarella, President of Assoenologi, such as market demand changes, organic wine development, export strategies, declining consumption, overproduction, international projects, and the gap with French competitors.

Over the past decade, Italy has seen a 125% increase in certified organic vineyard area, holding the global record with 117,000 hectares—18% of the national total. Could we be seen as global champions of organic wine, and are we effectively leveraging this leadership on international markets?

I’d say it’s slowly emerging. Where organic methods are applied scientifically in suitable territories—sunny, well-exposed hills—it ensures quality and sustainability. It’s a rising trend, especially as we better understand which areas yield optimal results. However, some producers, particularly in Sicily, don’t claim their organic practices. The risk/quality effort isn’t always rewarded in terms of product value.

This must not be overlooked—where organic practices are scientific and serious, there’s every reason to make it a communication focus.

Young people approach wine differently than past generations: they know fewer famous names, prefer to explore, moderate consumption, and seek experiential formats. What should wineries do in response to this shift?

This change began years ago, and we must remember that wine is cultural. Today, wine tells a story about our traditions and land. Smart, conscious consumption is part of loving wine—it’s no longer just a food product.

Young people want something different—look at the growth of wine tourism. They want to see the vineyards, visit wineries, then taste the wine. In the 1960s, we drank 130 liters per capita; now it’s 30. Wine is the symbol of our biodiversity, a cultural driver. Would a young person have asked these questions 40 years ago?

After high tariffs on Australian wine, France became China’s top supplier, helped by Bordeaux’s CIVB offices and a visit from President Macron. Has Italy fallen behind? What should our strategy be?

The French moved early while we rested on being the world’s top volume producer. They tell their story better—professionally and effectively. But we’re catching up. When an informed, unbiased consumer discovers our wine heritage, they often choose Italy. Our past mistakes include self-sabotage and internal rivalry instead of unity.

In both France and Italy, falling demand and overproduction remain major problems. The French estimate they need to uproot 15,000 hectares to fix the issue. Could this strategy work in Italy?

We’re already doing something similar, just less drastically. Most DOC grapes can be regulated by consortia. In Italy, we could apply this in chronically overplanted areas. But if we balance supply and demand, we can avoid drastic measures. Our farmers need a more entrepreneurial mindset—production management must align with the market.

You’re now involved in a major project to relaunch Georgian wine, the cradle of viticulture. Will this benefit Italy or create stronger competition globally?

Even if we wanted to stop it, we couldn’t—“rivers always flow to the sea.” Georgia transformed a climbing plant into a fruit-bearing tree. Unfortunately, they missed decades of cultural and enological updates. But their land is ideal. I accepted this challenge as a crowning career project. For someone like me, this is the ultimate reward.

I’m not worried about competition—wine isn’t an inert material. The same grape yields different wines depending on the terroir. We have our grapes, the Georgians have theirs.

The value gap with France is at a historic high: in 2022, Italy averaged €3.58/liter vs. France’s €8.80 (+16%). What can we do to close this gap?

Our DOC wines have improved a lot, but the gap is centuries old, not just decades. We must strictly balance supply and demand. Producers have two tools: improve quality and avoid producing more than the market needs. Overproduction forces prices down.

Many DOCs are already working on this. The issue is some producers struggle with these concepts—it’s a lack of entrepreneurship. Producers often focus on non-market issues, which hurts us. There’s a clear need for better market understanding.

This interview was conducted in partnership with Amorim Cork Italia as part of the “Amorim Wine Vision” project – a network of thought leadership on technical and topical wine-related issues, spotlighting the original visions of industry entrepreneurs and managers.

Key points

- Italy has a unique wine heritage but lacks a true entrepreneurial mindset.

- Italy leads in organic wine, but this strength is under-communicated.

- Producers must balance supply and demand to avoid overproduction.

- Younger consumers want wine experiences—authentic, not formal.

- France tells its wine story better; Italy must close this narrative gap.